There are many tremendous reasons for exploring Fort Pulaski National Monument in Georgia. Foremost is inside the wooden Sallyport gates. You will find yourself transported back in time to the American Civil War. Visit the grounds and witness staff and volunteers dressed in period garb bringing history to life on a guided tour. Fort Pulaski on Cockspur Island guards the two entrances of the Savannah River about 15-miles away from Historic Savannah, Georgia.

We did our self-guided tour during the Thanksgiving holiday and, amazingly, had very few others to contend with during our walk of the fort. The weather was overcast and chilly, and that may be the reason for way fewer crowds. Nevertheless, it made exploring and photographing so much easier.

This post may contain affiliate links, meaning if you purchase something through one of these links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you! Read the full disclosure policy here.

In 1833, they dedicated the fort to a Revolutionary War hero, General Casimir Pulaski. Noted as the father of the US Cavalry, the polish born nobleman was the inspiration for the name of Fort Pulaski. He died during the Battle of Savannah in 1779. They decommissioned the fortress in 1873.

Abandoned in the early 20th century, the fort to be a National Monument in 1924 by President Calvin Coolidge. After World War II, the Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service began the effort to repair the damaged fort.

Table of Contents

Getting to Fort Pulaski

This historic national landmark is situated just 15 miles south of Savannah and 5-miles south of the beautiful beaches of Tybee Island. On Cockspur Island overlooking the Savannah River, it is near several other historic forts, including Fort Sumter, Fort Moultrie, Old Fort Jackson, and Amelia Island’s Fort Clinch. The fort is an easy day trip.

- From Interstate I-95, take Exit 99 onto Interstate I-16 East (James L Gillis Memorial Hwy) for 7 miles.

- Take Exit 164A onto Interstate I-516 East toward US-80 East.

- Take Exit 3 (US-17 S/US-80 E) toward US-80 East.

- Turn left onto Ocean Highway, Ogeechee Rd (US-17 N, US-80 East).

- Bear right onto West Victory Drive (US-80 East).

- Continue on US-80 East for 13 miles.

- Fort Pulaski National Monument entrance will be on the left-hand side of US-80; the entrance is just after a turn in the highway.

Know Before You Go: Fort Pulaski National Monument

Before you step inside the historic walls of Fort Pulaski, here are a few helpful tips to make the most of your visit:

- Location: Fort Pulaski National Monument lies just east of Savannah, Georgia, on Cockspur Island—about a 20-minute drive from downtown Savannah and on the way to Tybee Island.

- Operating Hours: Open daily from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. Check the national park website for seasonal changes.

- Entrance Fee: $10 per adult (good for 7 days). Free with an America the Beautiful Pass, Every Kid Outdoors Pass, or Senior/Access Pass.

- Accessibility: The fort is partially wheelchair accessible, including some areas of the visitor center and fort interior. The trails and the drawbridge have uneven terrain—comfortable walking shoes are a must!

- Pets: Leashed pets are welcome on the trails and outside the fort, but not allowed inside the fort structure. There’s a designated pet walk area and plenty of shady paths for exploring with your pup.

- What to Bring: Sunscreen and a hat (limited shade inside the fort). Water bottle (especially if you’re hiking trails or visiting in warmer months). Binoculars or a camera—this is a top spot for birdwatching and photography.

- Trail Access: The monument includes several walking trails, including the Historic Dike Trail around the fort’s moat and the Lighthouse Overlook Trail with views of the Cockspur Island Lighthouse.

PRO Tip: Check the park schedule for cannon firings, ranger talks, and living history events. These are a highlight for visitors of all ages and offer a unique glimpse into 19th-century military life.

History of Fort Pulaski National Monument in Savannah

In the wake of the War of 1812, the United States undertook a profound commitment to safeguarding its coastal communities. This vision, known as the Third System, was a national project of care and protection, leading to the construction of 42 enduring fortifications along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

Among these stone sentinels are iconic sites like Fort Pickens, Fort Sumter, Fort Jefferson in Dry Tortugas and Fort Clinch. Designed as places of refuge and resilience, their most distinctive feature was walls of incredible solidity—built 11.5 feet thick with sturdy mortar to shelter those within.

Interesting Fact: The average thickness of walls at Fort Pulaski National Monument is between five and eleven feet.

Construction of this fort began in 1829 to protect the vital supply chain provided by the Savannah harbor. There is no doubt about the strategic significance of the Savannah harbor to the war effort. From 1829 to 1847, Fort Pulaski cost the federal government more than $1 million. During the construction of Fort Pulaski, 25 million bricks were used, all locally sourced from Savannah. Fort Pulaski saw only one major battle between Union and Confederate troops, with the Union winning and holding control until the end of the Civil War. General Robert E. Lee believed the fort was impregnable with its thick masonry walls surrounded by wide swaths of salt marsh.

And so it Begins-the Civil War battle at Fort Pulaski

On a cool April morning in 1882, a new era of warfare dawned over the fortress. From the distant shore of Tybee Island, nearly two miles away, Union artillerymen prepared a devastating barrage. They were armed with a terrifying new technology: the rifled cannon.

This weapon fired a spiraling projectile with horrifying accuracy over distances once thought safe. Instead of merely battering the massive 11.5-foot walls, the shells tore into them, ripping the sturdy masonry apart. Inside the fort, Confederate soldiers watched in stunned disbelief as their once-impregnable shelter was systematically shattered around them.

After enduring 30-hours of relentless and bloody siege, Colonel Charles Olmstead faced an impossible choice. Recognizing that their proud walls could no longer protect them, he surrendered. The development of the Parrott and James rifled cannons had, in a single day, rendered the mighty masonry forts of a past generation tragically obsolete.

Post U.S. Civil War

In the war’s aftermath, Fort Pulaski took on a somber new duty as a prison, its massive walls now confining former Confederate officials and Union deserters alike. For several years, the scarred fortress was patched and updated—new gun batteries and earthen mounds were added to its defenses. But by late 1873, the Army had withdrawn, leaving the fort officially closed. Only an ordnance sergeant and a lighthouse keeper remained, tiny figures within the vast, silent structure.

Though briefly reactivated during the Spanish-American War, when a small crew manned guns and electric mines at the river’s mouth, the fort was largely left to time and the elements for decades. It stood in quiet abandonment for most of the new century, until 1933, when it was entrusted to the care of the National Park Service, beginning its modern life as a preserved monument.

Discovering the Best Things to Do at Fort Pulaski

- Browse the Visitor Center and Gift Shop: Start your visit with a short film about the siege of Fort Pulaski. Pick up maps, junior ranger booklets, and Civil War-era souvenirs.

- Explore the Historic Fort Interior: Walk through vaulted brick chambers, drawbridges, and bastions. See original Civil War battle damage and artillery. Learn from interpretive displays and museum exhibits inside the fort.

- Watch a Cannon or Musket Demonstration: Experience live historic weapon demonstrations on select weekends. Check the schedule at the visitor center for times.

- Walk the Moat and Outer Fort Walls. Stroll around the moat for panoramic views and unique photo ops. See how the fort’s design protected it during wartime. Spot birds and wildlife in the surrounding marsh.

- Hike the Lighthouse Overlook Trail> Easy, scenic trail with views of the Cockspur Island Lighthouse. Ideal for birdwatching and enjoying coastal breezes. A peaceful contrast to the fort’s structured interior.

- Have a Picnic Beneath the Oaks. Shady picnic areas with tables are near the parking lot. Enjoy lunch under Spanish moss-draped trees. Restrooms and water fountains are nearby.

- Go biking on the historic dike trails: bring your bikes and ride the gravel dike road system. Offers unique views of the Savannah River and fort exterior. Great for active visitors looking to explore more of the grounds.

Always start with a walk through the Visitor Center

The visitor center is open daily from 9AM until 5PM. Many of the exhibits are a living history of the American Revolution. We made a stop to watch the 20-minute video, “The Battle for Fort Pulaski” which plays every 1/2 hour throughout the day. It is an interesting exploration of the history of Fort Pulaski from its construction through the end of the 20th century.

We always check our passport stamps and look through the exhibits. Kids can complete their own Junior Ranger booklets, earning their badges.

Self-Guided Tour of the Interior of Fort Pulaski National Monument

We started our self-guided tour at the Sallyport entrance to the fort after picking up a self-guided tour brochure of Fort Pulaski at the Visitor’s Center. This 30-60 minute tour has 14 stops that open a window through the centuries of the fort’s intriguing past. You can also learn more about Fort Pulaski through ranger-led tours offered daily, beginning under the pecan tree on the parade grounds.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #1: Sallyport & Drawbridges

Access to the fort was granted only through the sallyport, a gateway defended by a formidable drawbridge. This entrance was uniquely protected by a heavy wooden portcullis—a massive, iron-bound grille suspended above the threshold. Using a system of winches and counterweights, soldiers could raise this immense gate or lower it with a decisive crash to seal the passage.

To enter, one had to walk beneath this formidable barrier, proceeding up a narrow, granite-lined archway. The path was watched by ten rifle slits piercing the walls, ensuring anyone passing through remained in the defenders’ sights. The journey ended at another set of imposing, bolt-studded doors, completing a passage designed for absolute control.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #2-Gorge Wall-Venture Through Into Lower Level

They also nicknamed it the “throat” of the fort because of the sallyport entrance. The gorge or rear wall of the fort houses all the living quarters. Walking under the covered veranda that runs the entire length of the gorge, it protected the troops from the hot Georgia sun. The surrounding casements contained the enlisted barracks, officer quarters, gunnery galleries and storage facilities. The parade grounds are directly in front of the veranda.

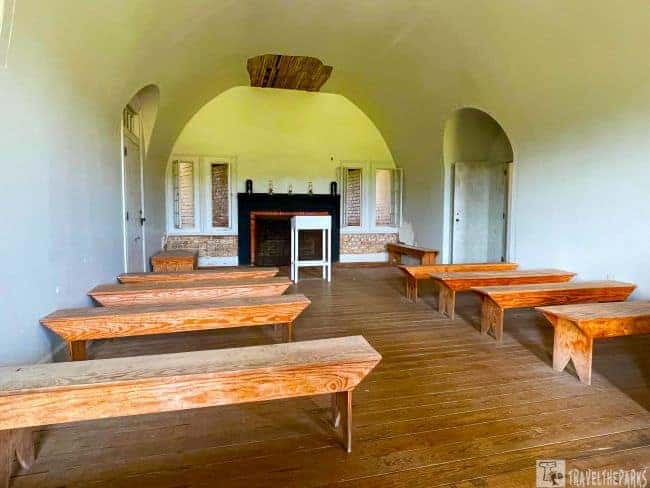

Interconnected archways linked many of the casement rooms along the Gorge wall. The officer’s mess, commanding officer’s quarters, chapel, and the medical infirmary. Each room in the small Confederate chapel and medical infirmary was authentic with all the period furnishings. It was like stepping back in time. The chapel illustrates the importance of religious services for the soldiers and officers stationed at the post.

The Fort Pulaski Parade Ground

The fortress walls stretch for over a quarter-mile, encircling a sweeping, two-and-a-half-acre parade ground. Dominating this interior space are the graceful half-moon arches of 60 casemates, each vaulted chamber designed to house a heavy cannon behind protective, wood-framed doors. A six-pound cannon, which was built to defend the drawbridge, remains positioned before the sallyport, standing sentry at the main entrance, aimed across the drawbridge.

They stationed soldiers at the fort from 1847 to 1873. The soldiers exercised, practiced drills, and a weapons firing. Occasionally, the parade grounds hosted special events for the soldiers during their off-duty time. Some soldiers played baseball, enjoyed sack and wheelbarrow races or other activities. Followed by lively music and feasting late into the evening.

Watch a live cannon demonstration at Fort Pulaski

If you’re lucky, re-enactors will hold a musket demo and cannon firing during your visit! Weapons demonstrations with the firing of Civil War-era muskets and cannons. We learned that during battle, General Robert E. Lee ordered that trenches be dug across the parade ground. This would prevent cannonballs from landing inside the fort.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #3-The Barracks

During the Civil War, the fort’s population swelled to nearly 600 soldiers. To accommodate this influx, many of the empty casemates were converted into barracks. The once-spacious gun chambers became crowded living quarters, with triple-decker bunk beds lining either wall. In this tight arrangement, six men shared a single bunk space, sleeping in the top, middle, and bottom berths.

The only comfort against the coastal chill and damp was a small woodstove or fireplace in each room. This modest hearth was a vital center for warmth, drying uniforms, and a brief respite from the unyielding stone walls that now served as both fortress and home.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #4-The North powder magazine

Fort Pulaski had two powder magazines that stored all the gunpowder and munitions for the fort’s artillery. The windowless room comprises 12 to 15 foot thick cedar lined walls. The magazines housed large barrels, each containing 100 pounds of powder. Bags of chloride of lime hung from the rafters above to cut down on the moisture. During the 30 -hour siege of the fort by the Union, Confederate soldiers feared the 40,000 pounds of gunpowder in the Northwest magazine would explode after a projectile hit the roof.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #5-Northwest Bastion

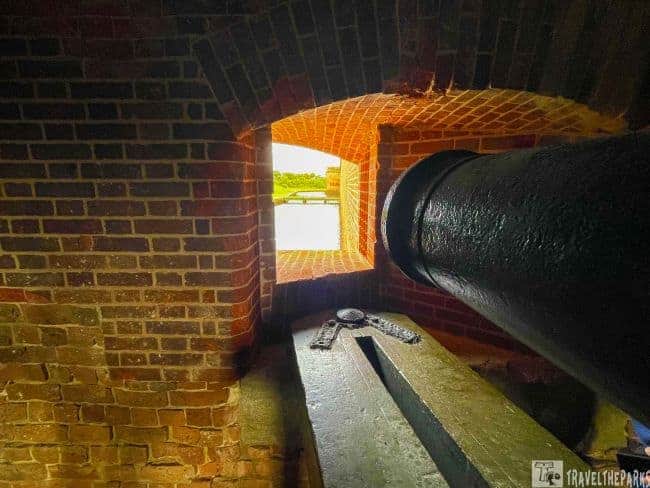

Fortifications such as Fort Pulaski. comprise bastions, which extend from the main wall and have embrasures and loopholes. They remind me of a medieval castle. Joseph Gilbert Totten modeled Fort Pulaski’s embrasures after an 1815 design. Embrasure openings were 10 square feet, protecting the soldiers responsible for loading the cannons. Embrasures allowed for crossfire. Loopholes were narrow slits in the walls for artillery.

Interesting fact: Fort Pulaski’s bricks were made primarily by enslaved men, women, and children. In some cases, fingerprints or even handprints were left on bricks while they were being made. If you look closely at the bricks, you can see them.

Forts could defend themselves with flanking (lateral) fire. When an enemy tried to storm the fort through the western gorge wall, the demi-bastions created a crossfire. In the ceiling, we could see small smoke vents just above the embrasures. Iron trekked grooves on the floors of the casements allowed the wheeled cannons to be repositioned in a circular motion.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #6 Gun Galleries

This casement houses gun galleries. sling carts, and the gin. At casement #47, we saw a couple of the original sling carts. What are sling carts? Union soldiers used sling carts to manoeuvre the 17,000 mortars and cannon barrels over difficult terrain such as the salt marsh. The large wheeled carts did not use horses. Instead, enlisted men pulled each cart. There were often 250 men needed to harness a cart to carry these loads because they were so heavy.

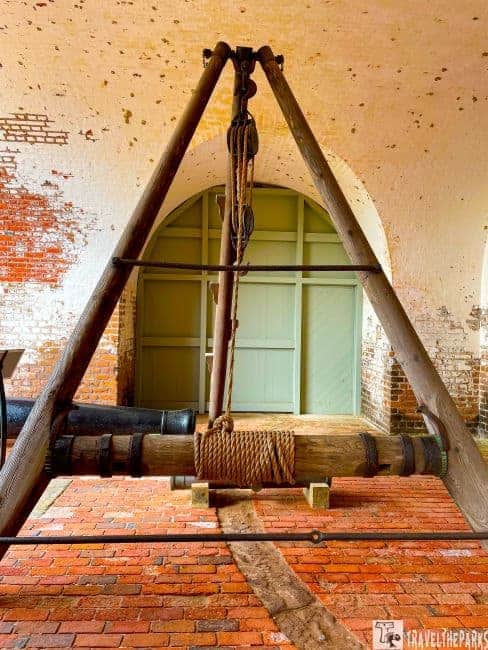

At casement #40, we learned about what job the gin performed. The sheer size of the cannons made lifting them nearly impossible without the help of the gin (gun hoist). They made gins from two wooden legs fastened by a third leg known as a pry pole (a tripod). Typically, the cast iron cannons’s barrels had a weight of over 10,000 pounds. The hoist used a lever and pulley system to raise/lower the cannon to the parapet, employing a unit of 10 men and an officer (non-commissioned). The Field and Siege, the Garrison, and the Casemate Gin were the different gins used in the mid-nineteenth century.

The Blindage-What is it?

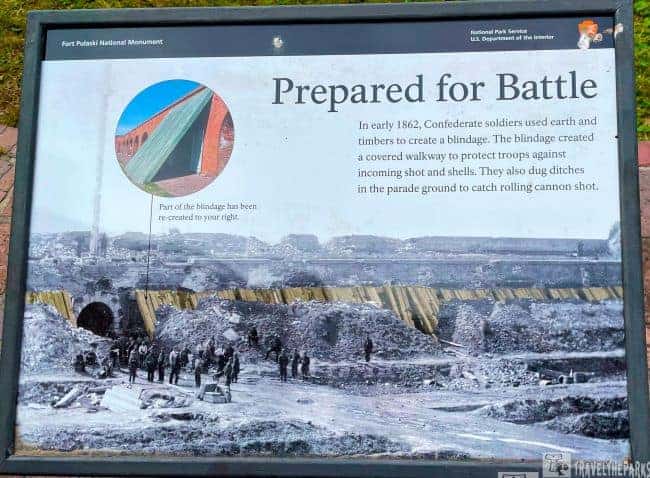

In order to protect the interior walls of the fort, Confederate soldiers built blindages out of timber laid up against the walls. There is a secure alleyway between the blindage and the casemates created by these walls. Their purpose is to protect the men from explosive shells and errant cannonballs.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #7 The Water System

It is interesting to see the 10 cisterns/storage tanks below the casements used to store water. When rainstorms occur, they collect water from the fort. The water seeps through three feet of earth and one foot of oyster shells before reaching the lead-covered brick roof. Cisterns are then filled directly with water. Weep holes in the walls facing the parade ground collect overflow water from the roof. The entire system holds more than 200,000 gallons of fresh water.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #8 & 9-The Upper Level Terreplein & Terreplain (East Angle)

At the northwest corner of the fort, we climbed some stone steps to the top of the terreplein. So what is a terreplein? The information placard described them as brick and granite platforms that are mounted on top of the ramparts of the fort. On top of the fort, the terreplein is a flat space between the parapet and the parade face. The short wall was the only protection for cannon crews. They designed parapet walls with recesses so that cannon carriages could swing freely. From the top, cannons could fire farther than those in casemates below.

We gazed across at the distant shore of Tybee Island, imagining what it was like the morning of the attack. The overcast day only made the image more vivid in our minds. The ten James and Parrot rifled cannons were fired from two batteries near the western end of the island. Union forces spaced additional artillery along the beach, two miles distant. We could see the beam of the lighthouse shining out over the water.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #10-The Prison

In 1864, Fort Pulaski’s role darkened as it became a prison for several hundred captured Confederate soldiers. Conditions within the garrison were brutal and inhumane. The men suffered from severe shortages of food, a lack of medical care, and the deprivation of basic necessities. In this grim environment, disease claimed the lives of thirteen prisoners, who were laid to rest in the post cemetery.

This group of soldiers, enduring such profound hardship, later became known as the “Immortal 600.” After their ordeal at Pulaski, many were transferred north to the notorious Fort Delaware, carrying with them the scars of their suffering.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #11-The Breach

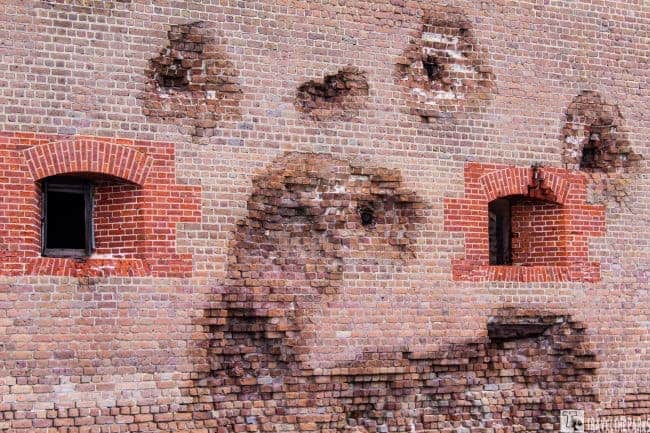

During the attack of the fort by Union troops, they used 36 rifled cannons, including the new James & Parrot Rifled Cannon. Using the newly developed cannon, Union forces demolished a corner wall of the fort within 30 hours. They rebuilt the three casements on the southeast wall after the Confederate surrender. The 48th New York Volunteers completed the work in 1862 without embrasures.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #12-Southwest Bastion

This area was impressive. Signage explains that a fire destroyed the wooden floors in 1895. The floors did not need to be replaced, since the fort was abandoned. Several layers of sediment hide the brick piers that extend up from the wooden grillage. In the marshy terrain of Cockspur Island, wooden pilings extend up to 70 feet below the grillage. Despite being completely encased in mud, the pilings remain in place today.

We found the embrasure for casement #16 in the southwest corner of the fort. The embrasure demonstrates just how thick the walls are. Heavily damaged during the April 1862 bombardment, this corner embrasure hosts slave fingerprints that are still visible from the time of construction. In the aftermath of artillery damage, removal of the upper layer of bricks revealed fingerprints and handprints. They found Savannah made grey bricks on the lower portion of the wall. Molded at the Hermitage plantation. They exclusively used enslaved men, women, and children to make the bricks.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #13-Headquarters-Surrender Room

The quarters of Confederate commanding officer, Col. Charles Olmstead, this is where on April 11, 1862. He surrendered to the Union after a 30-hour bombardment. They restored the room in 1935 after a lightning strike caused a fire that destroyed much of the officers’ quarters.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #14-Cistern Room

The Cistern Room was the key to the survival of the fort. Cisterns collected water in waterproof reservoirs for use. They built Fort Pulaski with 10-cisterns that held nearly 200,000 gallons of water. Using gravity to pull the water down, they filtered it through a bed of oyster shells and sand. There it collected in a valley created by the casemate arches. A layer of brick and lead sheeting waterproofed the arches. The pooled water filled a channel and completed its journey to the brick cistern below through pipes placed in the masonry walls.

Fort Pulaski Self-Guided Walk Stop #15-The Impressive Fig Tree

The most incredible find inside is the mass of a giant fig tree that sprawls across the parade grounds. Planted in the 1890s by the lighthouse keeper, it has sustained itself for 130 years through many hurricanes. In the warmer summer months, samples of the fruit are available.

Guided Walking Audio Tour Outside Perimeter-Fort Pulaski

Beyond its historic walls, the fort is surrounded by over five acres of scenic landscape, featuring several inviting trails. For a gentle walk, the paths to the Cockspur Lighthouse or along the North Pier offer relatively easy exploration with beautiful views.

The area also connects to the much longer McQueen’s Island Historical Trail, which ultimately spans over 100 miles along the historic coastal route. Please note that while the full trail is listed at 111 miles, currently only the first two miles from the fort are accessible to visitors, as subsequent sections are under construction for future access.

Exterior Walk Stop #16-The Moat

This is the initial bridge crossing the moat to the fort entrance. Surrounded by an 8-foot deep moat, its width was 32-38 feet. The waters of the Savannah River filled it, controlled using tidal gates. It was the first line of defense. Crossing the footbridge, it connects the demilune before reaching the drawbridge and the sallyport entrance at the Gorge Wall (western rear of the fort). The addition of earthen fortifications of the demilune in 1872 houses tunnels leading to multiple powder magazines. During the Civil War, the demilune was flat and included gun platforms, kitchens, mess rooms, storage areas and a guardhouse.

Exterior Walk Stop #17-The Demilune

Our outside walk of the fort grounds started at the Demilune. It obscures the fort from the visitor center. They built the Demilune to protect the Gorge wall (longest wall of the fort), which is also the rear main entrance. Demilune, which means ‘half-moon’ in French, was originally flat, with storage sheds and outbuildings, surrounded by an impressive array of cannons. In the aftermath of the Civil War, they constructed the earthen mounds.

Exterior Walk Stop #18-The Breached Corner

The southwest wall saw the most devastation. Outside the fort, you can see the breached corner, evidence of the shelling. In 1862, crews repaired the southeast angle breach using bright-red brick, replacing the original brown brick. This vivid patchwork still clearly shows where the siege mortars struck. Most of the cannonballs and projectiles embedded in the stone of the southeastern wall facing Tybee are still visible today.

Exterior Walk Stop #19-The Cemetary

As part of Pulaski’s construction, they established a small cemetery alongside the demilune moat. Soldiers, workers, and their families are buried at Fort Pulaski’s cemetery. In the past, Union soldiers and Confederate troops and those who built the fort and supported the garrisoned troops shared this land.

Exterior Walk Stop #20-South Channel and the Marsh

In the early 1800s, Robert E. Lee built a dike system to keep freshwater inside and saltwater out of Fort Pulaski. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps came in to restore Fort Pulaski from its abandoned state and planted trees around the island to beautify the space. Today, the South Channel canal and feeder canals still provide water for the moat through tidal sluice gates.

What are the best outdoor activities at Fort Pulaski National Monument?

Venture Down the North Pier Trail

An easy paved trail travels through a wooded setting. This trail passes through a portion of the original Fort Pulaski settlement. There is a 1/4 mile trail that highlights Battery Hambright from the late 19th century, as well as the historic north pier.

The Construction Village-A young Second Lieutenant of engineers, Robert E. Lee, arrived in 1829 to oversee the project of building the fort. Cockspur Island was remote and accessible only by boat. All materials and supplies need to be brought to the island and stored. In 1862, the bustling village was an extension of the fort itself, with a general store, blacksmithery and a bakery. They posted a depiction of the village on an interactive kiosk, which helps you envision how the site must have looked. They abandoned the village in 1880.The hurricane of 1881 destroyed most of the structures, leaving only two cisterns from the construction village. These cisterns once collected fresh rainwater for the troops.

Adjacent to the construction village, the Contraband Camp provided shelter for a community of African American refugees who had escaped slavery. The living quarters for carpenters, cooks and general laborers during the 1829 construction of the fort. Later, after the battle of Fort Pulaski (1862) the Union gave them freedom. Many sought safety on Cockspur Island, living in the contraband camp until the Civil War ended. It was eventually abandoned. All that is visible today is the cistern holding tank covers.

The Fortifications of Battery Hambright

Workers constructed the concrete and earthen battery to shore up the defense of the abandoned fort during the Spanish-American War. It housed two guns. It is only a mile from the masonry fortress. The Spanish never reached the Savannah River, and they ultimately left the island to the forces of nature.

The Georgia Society, Colonial Dames of America, erected the John Wesley Monument in 1951 to commemorate the landing on Cockspur Island, February 6, 1736.

Explore with a hike on the Lighthouse Overlook Trail

Beginning just outside the visitor center, the trailhead begins at the end of the parking lot. The Cockspur lighthouse is the major attraction at the southeastern end of this 1-mile out-and-back trail. From approximately 200 yards away, hikers can view the lighthouse. Marking the South Channel of the Savannah River, they shape its unique base like a ship’s prow to reduce the impact of waves and currents on the structure. At high tide, the rising water completely isolates the lighthouse, transforming it into a solitary sentinel surrounded by the sea. Low tide reveals the oyster bed that connects the lighthouse to the island.

On the southeastern side of the island, along the south channel of the Savannah River, is the Cockspur Lighthouse, built on an oyster shell bed. The original marker was just that, a marker built in 1837. They added a light to the brick tower around 1849 to ease navigation. An immense hurricane in 1854 destroyed the 46-foot lighthouse. Replaced in 1856, it incorporated a fifth-order Fresnel lens. The lighthouse continued to light the way until 1909, when the redirection of river traffic to the north channel ended its service. In this way, the beacon’s active operation came to an end (decommissioned). Re-illumination began in 2007 primarily for historical reasons rather than navigational ones.

What to Bring on Your Hike?

Be sure to wear long sleeves, long pants, pack sunscreen and insect repellant. We suggestion to go during the winter months when the bugs aren’t so bad. It gets hot in the summer, and you’ll dehydrate before you know it. Bring water and a snack even if you’re going for a short hike.

Note: We combined this trip with Cumberland Island National Seashore and Fort Frederica National Monument. We included a side-trip to Congaree National Park.

Final Thoughts on Epic Reasons to Explore Fort Pulaski National Monument in Georgia

The culturally rich state of Georgia contains various historical national monuments reflecting its variability in heritage. It finds prominence with the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta and is dedicated to his life and legacy as one of the leading people in the movement for civil rights. The Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he was a preacher; his childhood home; the King Center, where he was entombed-it’s all here in one park. Other important sites include the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park in Macon, which preserves the remains of ancient Native American cultures, including burial mounds and ceremonial sites dating back over 12,000 years. These are just a few reasons to spend time in Georgia.

Fort Pulaski is more than just a fort! Visitors to Savannah and Tybee Island will find plenty to enjoy at this well-preserved garrison. The exploration of Fort Pulaski is without a doubt one of the most iconic activities on the Georgia coast, and you shouldn’t miss it!

Have you had the opportunity to visit this magnificent fort? What historic takeaway did you have? Share your impressions with us in the comments below.